Ne’er-do-wells leaked personal data — including phone numbers — for some 553 million Facebook users this week. Facebook says the data was collected before 2020 when it changed things to prevent such information from being scraped from profiles. To my mind, this just reinforces the need to remove mobile phone numbers from all of your online accounts wherever feasible. Meanwhile, if you’re a Facebook product user and want to learn if your data was leaked, there are easy ways to find out.

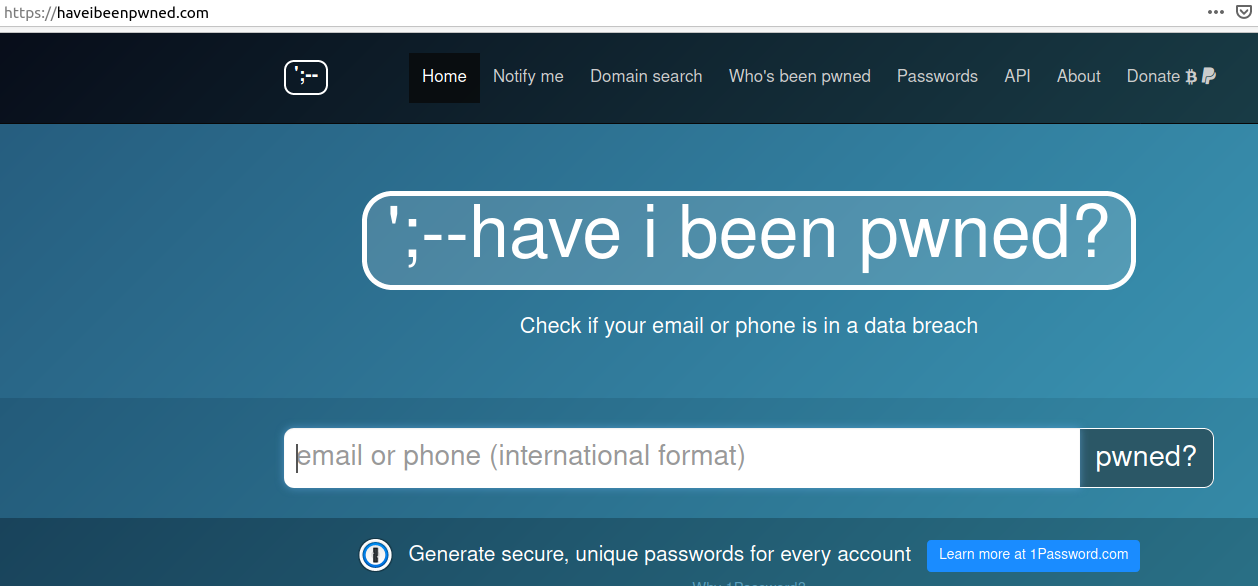

The HaveIBeenPwned project, which collects and analyzes hundreds of database dumps containing information about billions of leaked accounts, has incorporated the data into his service. Facebook users can enter the mobile number (in international format) associated with their account and see if those digits were exposed in the new data dump (HIBP doesn’t show you any data, just gives you a yes/no on whether your data shows up).

The phone number associated with my late Facebook account (which I deleted in Jan. 2020) was not in HaveIBeenPwned, but then again Facebook claims to have more than 2.7 billion active monthly users.

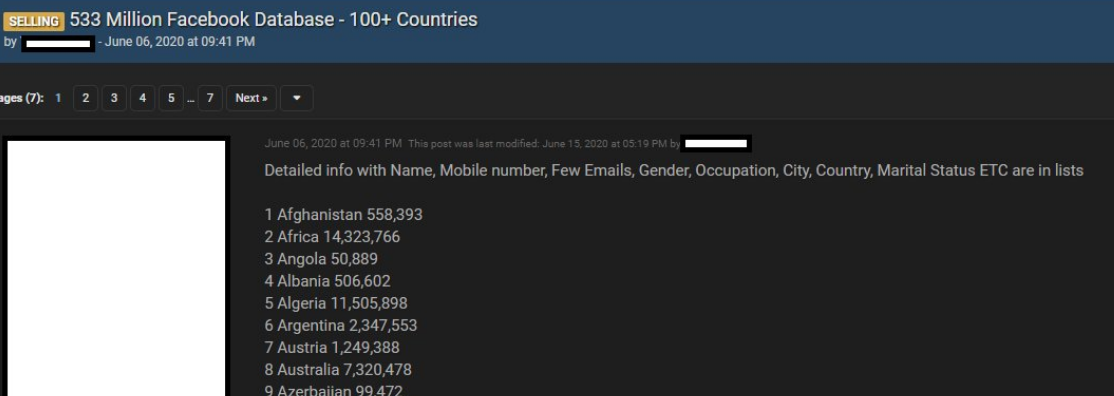

It appears much of this database has been kicking around the cybercrime underground in one form or another since last summer at least. According to a Jan. 14, 2021 Twitter post from Under the Breach’s Alon Gal, the 533 million Facebook accounts database was first put up for sale back in June 2020, offering Facebook profile data from 100 countries, including name, mobile number, gender, occupation, city, country, and marital status.

Under The Breach also said back in January that someone had created a Telegram bot allowing users to query the database for a low fee, and enabling people to find the phone numbers linked to a large number of Facebook accounts.

A cybercrime forum ad from June 2020 selling a database of 533 Million Facebook users. Image: @UnderTheBreach

Many people may not consider their mobile phone number to be private information, but there is a world of misery that bad guys, stalkers and creeps can visit on your life just by knowing your mobile number. Sure they could call you and harass you that way, but more likely they will see how many of your other accounts — at major email providers and social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, e.g. — rely on that number for password resets.

From there, the target is primed for a SIM-swapping attack, where thieves trick or bribe employees at mobile phone stores into transferring ownership of the target’s phone number to a mobile device controlled by the attackers. From there, the bad guys can reset the password of any account to which that mobile number is tied, and of course intercept any one-time tokens sent to that number for the purposes of multi-factor authentication.

Or the attackers take advantage of some other privacy and security wrinkle in the way SMS text messages are handled. Last month, a security researcher showed how easy it was to abuse services aimed at helping celebrities manage their social media profiles to intercept SMS messages for any mobile user. That weakness has supposedly been patched for all the major wireless carriers now, but it really makes you question the ongoing sanity of relying on the Internet equivalent of postcards (SMS) to securely handle quite sensitive information.

My advice has long been to remove phone numbers from your online accounts wherever you can, and avoid selecting SMS or phone calls for second factor or one-time codes. Phone numbers were never designed to be identity documents, but that’s effectively what they’ve become. It’s time we stopped letting everyone treat them that way.

Any online accounts that you value should be secured with a unique and strong password, as well as the most robust form of multi-factor authentication available. Usually, this is a mobile app like Authy or Google Authenticator that generates a one-time code. Some sites like Twitter and Facebook now support even more robust options — such as physical security keys.

Removing your phone number may be even more important for any email accounts you may have. Sign up with any service online, and it will almost certainly require you to supply an email address. In nearly all cases, the person who is in control of that address can reset the password of any associated services or accounts– merely by requesting a password reset email.

Unfortunately, many email providers still let users reset their account passwords by having a link sent via text to the phone number on file for the account. So remove the phone number as a backup for your email account, and ensure a more robust second factor is selected for all available account recovery options.

Here’s the thing: Most online services require users to supply a mobile phone number when setting up the account, but do not require the number to remain associated with the account after it is established. I advise readers to remove their phone numbers from accounts wherever possible, and to take advantage of a mobile app to generate any one-time codes for multifactor authentication.

Why did KrebsOnSecurity delete its Facebook account early last year? Sure, it might had something to do with the incessant stream of breaches, leaks and privacy betrayals by Facebook over the years. But what really bothered me were the number of people who felt comfortable sharing extraordinarily sensitive information with me on things like Facebook Messenger, all the while expecting that I can vouch for the privacy and security of that message just by virtue of my presence on the platform.

In case readers want to get in touch for any reason, my email here is krebsonsecurity at gmail dot com, or krebsonsecurity at protonmail.com. I also respond at Krebswickr on the encrypted messaging platform Wickr.